🧦Renfro Corporation. Short Rancid Socks.🧦

Kelso & Company-owned Renfro Corporation Struggles

The pandemic has been tough on all of us but one benefit is that we no longer have to see short-pants-wearing hedge fund and investment banker DBs strut through midtown Manhattan showing off their stupid frikken “sock game.” “Oooh, I love your socks, want to party?” said no person anywhere ever. So, small victories.

Speaking of losers, North Carolina-based Renfro Corporation is a Kelso & Company-backed* manufacturer of socks and the cotton behind partner brands like Fruit of the Loom, New Balance, Dr. Scholl’s, Carhartt, and Sperry as well as its own brands KBell, Hot Sox and Copper Sole. They produce exciting threads like these:

And when they really want to get cray cray, they spice things up with … well … whatever the hell this is supposed to be:

For the record, these socks — which, we think, show fruit(?) (see what they did there?) — have zero reviews. We reckon that’s because there isn’t a human being on earth who actually bought them, let alone reviewed them. Seriously, who green lit these things? Whomever it was has, at best, zero design sensibility and, at worst, psychopathy. Just sayin'.

The company’s capital structure is looking a bit deranged too — enough so that Moody’s slapped a fierce downgrade on the company (Caa3) back in late August. The cap stack consists of:

an $87.4mm asset-backed revolving credit facility due February ‘21;

a $20mm senior secured priming term loan due February ‘21 (Caa1); and

a $132mm secured first lien term loan (Caa3) due March ‘21 that bids in the low 30s.

In connection with securing the priming term loan, the company obtained an extension of a limited waiver related to going concern language in its most recently audited financial statements to October 31, 2020. So, there’s a potential catalyst on the horizon. Shortly thereafter, there are the maturities. February and March are right around the corner. 😬

Per Moody’s:

Renfro's Caa3 CFR reflects the company's weak liquidity and risks regarding the company's ability to refinance its upcoming debt maturities given recent performance challenges and high financial leverage.

As of April 2020, lease adjusted debt/EBITDAR stood at around 6.4 times, and funded debt to credit agreement EBITDA was around 5.9 times. Recent unprecedented disruptions caused by the global coronavirus pandemic will likely challenge the company's ability to significantly reduce leverage over the very near term when it needs to refinance maturing debt. The rating also incorporates the company's modest revenue scale relative to the global apparel industry, significant customer concentration, and narrow product focus. With regard to financial strategy, in Moody's view, given a low equity valuation, private equity sponsor Kelso & Company, L.P. is unlikely to provide any sponsor equity support . Supporting the rating are Renfro's well-recognized licensed brands, long-term customer relationships and the relatively stable nature of the socks business. (emphasis added)

Moody’s appears a bit forgiving here. This company had plenty of challenges to deal with before COVID heightened things. First, while the company does boast of some US-based manufacturing, a significant amount of its supply chain is dependent upon Asia which, thanks to trade conflict with China, was likely already under strain. Second, a significant amount of its business is done through Walmart Inc. ($WMT). While on one hand this is a positive given Walmart’s recent performance, y’all know how we feel about too much customer concentration. Third, there’s this from Renfro’s website:

The company’s respected name, integrity, and innovation have fostered solid, trusted relationships with the world’s biggest retailers, including Wal-Mart, Kmart, Macy’s, Costco, J.C. Penney, Sears, and Target, to name a few. It is considered the category captain by several retailers.

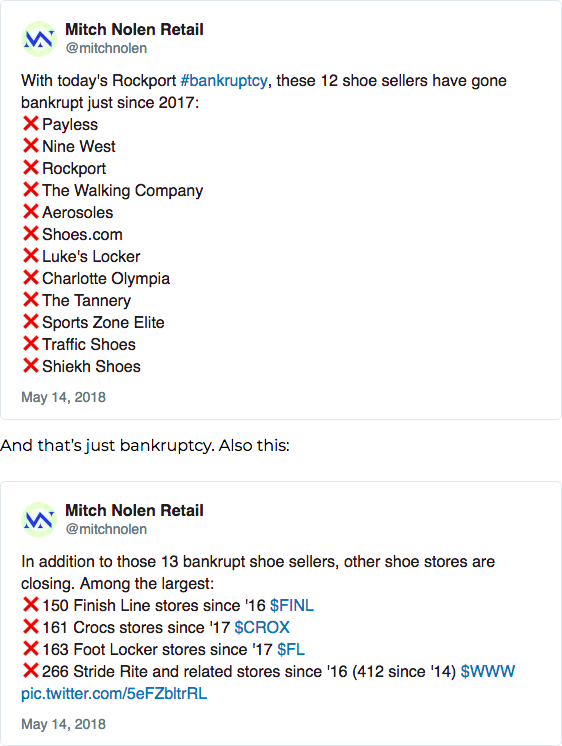

Call us “deranged” but now doesn’t seem to be a great time to over-index to Kmart, Macy’s Inc. ($M), J.C. Penney or Sears. The decline of the department store is obviously trouble for a lot of different “mall-adjacent” products but especially so for products that Renfro CEO Stan Jewell himself described as an "afterthought." Less foot traffic equals fewer impulse purchases of socks (that just happen to be conveniently located near cash registers). Any product that benefits from being an add-on as part of a larger shopping trip will feel the #retailapocalypse especially hard.

This is where the company’s “narrow product focus” bites. The company only makes socks and not much more. Attempts to generate revenue elsewhere didn’t go all-too-well: back in May, for instance, the state of Tennessee paid the company $8.2 million to deliver cloth masks. Renfro stepped up producing millions of made-in-America cloth masks on short notice. The reception was … a bit … cold:

It also doesn’t help that the company has upstart sock competitors nipping at its feet. Renfro is a ~$500 million player in a market orders of magnitude larger than that. Though socks on the whole are far from a growth category there is a strong shift in mix towards fashion-oriented socks. As Mr. Jewell has pointed out, maybe you "…like pizza and beer so I’m going to have pizza and beer on my socks [and] like Picasso, so I’m going to have Picasso on my socks." Or maybe you get a pair or socks with a massive middle finger on it. Does Renfro sell those? 🤔

Renfro has tried to capture some of this category. But they were a little late to the party. Companies like Stance and Bombas didn’t exist a decade ago and are now each reportedly doing hundreds of millions in revenue and, in the case of Stance, partnering with the likes of Billie Eilish and the MLB. Their growth comes at the expense of slower moving, less well funded players like Renfro. And there is also a horde of other brands (e.g., Allbirds) and generic D2C “blands” with missions to "change the rules on how socks work” funded by growth-at-all-cost venture investors focused on customer acquisition everywhere but the mall. A strong relationship with J. C. Penney won't do much to combat these headwinds.

Renfro has a tough few months ahead of it. The work-from-home trend won’t help matters either. But, perhaps Moody’s underestimates Kelso and they’ll write another check. Crazier things have happened. But Renfro will likely have to show that they have a strategy to combat the perfect storm swirling around it.

*Kelso acquired the company in 2006 — an oddly hot year for the sock industry. That same year Blackstone took Gold Toe private and scooped up rival Moretz. Blackstone exited the investment in 2011 with a $350mm sale to Gildan Activewear Inc. ($GIL) in 2011.

The company is also 25% owned by Japanese conglomerate Itochu Corp. ($ITOCY), one of five companies recently invested in by Warren Buffett. Looks like Berkshire Hathaway ($BRK.A) just can’t stay away from its textile roots.