And so we asked:

Given all of that, would you want Rockport’s brick-and-mortar business?

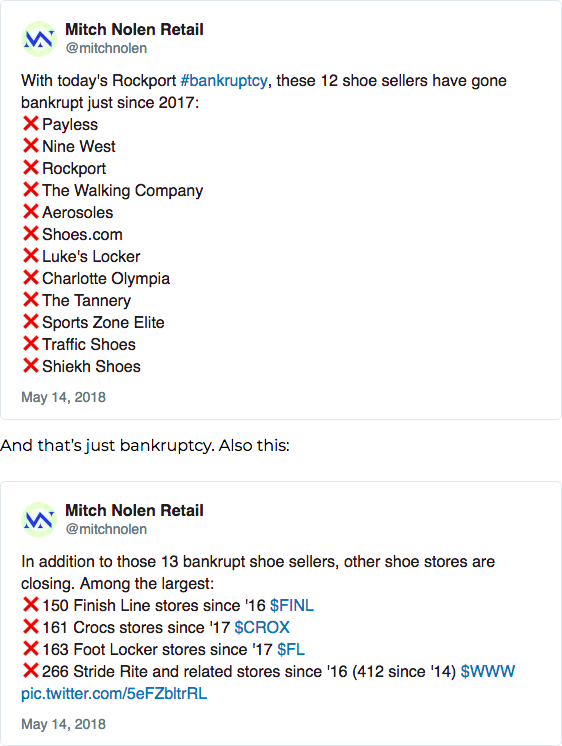

Answer: no. Apparently nobody did. And, in fact, nobody — other than the stalking horse, CB Marathon Opco, LLC — wanted any part of Rockport’s business.

On July 6, the company filed a notice that it cancelled its proposed auction. There were no qualified bidders, it noted, thereby making CB Marathon Opco, LLC the winning bidder by default. And given that the stalking horse agreement excluded the U.S. brick-and-mortar assets, those assets are now officially kaput. A hearing at which the bankruptcy court will bless the sale is scheduled for July 16. Aside from some additional administrative matters in the case, that hearing will mark a wretched ending for a company founded in the early 1970s.

*****

Juxtapose that doom and gloom with this Techcrunch piece about the rise of venture capital in footwear:

Over the past year-and-a-half, investors have tied up roughly $170 million in an assortment of shoe-related startups, according to an analysis of Crunchbase data. The vast majority is going to sellers and designers of footwear that people might actually want to walk in.

Top funding recipients are a varied bunch, including everything from used sneaker marketplaces to high-end designers to toddler play shoes. Startups are also experimenting with little-used materials, turning used plastic bottles, merino wool and other substances into chic wearables.

The piece continues:

It should be noted that recent footwear funding activity comes on the heels of some positive developments for the shoe industry.

Positive developments huh? “Some” must be the operative word given the preface above. There’s more:

First, this is a huge and growing industry. One recent report pegged the global footwear market at $246 billion in 2017, with annual growth rates of around 4.5 percent.

Second, public markets are strong. Shares of the world’s most valuable footwear company — Nike — have climbed more than 50 percent over the past nine months to reach a market cap of nearly $130 billion. Stocks of several smaller rivals, including Adidas, have also performed well.

Third, men are spending more on footwear. Though they’ve long been stereotyped as the gender with more restrained shoe-buying habits, men are putting more money into footwear and could be on track to close the spending gap.

And:

…one other bullish sneaker trend footwear analysts point to is the changing buying habits of women. Driven perhaps by a desire to walk more than a few blocks without being in pain, we’re buying fewer high heels and more sneakers.

The piece goes on to list a lineup of well-funded footwear companies. In marketplaces, GOAT and StockX. In streetwear, Stadium Goods. For children, Super Heroic. For comfort, Allbirds, Rothy’s, and Birdies. And the article neglected to mention Koio, Greats, and M. Gemi, to name a few. If you feel as if these names are unfamiliar because you didn’t see them at a brick-and-mortar footwear retailer in your last trip to the mall, well…yeah. That ought to explain a lot.

Interestingly, before unironically asking (and not entirely answering) whether any of these companies actually make money, the article also highlights Tamara Mellon,“a two-year-old brand that has raised more than $40 million to scale up a shoe design portfolio that runs the gamut from flats to spike heels.” Indeed, the company recently raised a $24mm Series B round* to grow its Italian-made pureplay e-commerce direct-to-consumer brand. In reality, though, Tamara Mellon is only technically two years old. It was around before 2016. In a different iteration. That iteration filed for bankruptcy.

In early 2016, Tamara Mellon Brand LLC filed for bankruptcy because of a liquidity crisis. And it couldn’t sufficiently raise capital outside of a chapter 11 filing to ensure its survival. After filing for bankruptcy, the company took on a $2mm debtor-in-possession credit facility from Ms. Mellon and, after combatting an equityholder-led “recharacterization”** challenge (paywall), swapped its term loan debt into equity. Winning prepetition equityholders like Ms. Mellon and venture capital firm New Enterprise Associates (NEA) came out with 16 and 31.1 percent of the equity, respectively. In turn, NEA capitalized the company to the tune of approximately $12mm.

Which highlights the obvious: not all of these companies will ultimately have renowned founders who merit second chances. A number of these high-flying e-commerce upstarts will fail; some of them will file for bankruptcy. The question is: as the funding rounds pour in from venture capitalists looking for the next big exit, how many other brands and shoe retailers will they push into bankruptcy first?

*****

*In October 2017, we wrote the following in “Sophia Amoruso's Nasty Gal Failure = Trite Lessons (Short Puffery)”:

We love how entrepreneurs are all about "move fast and break things" and "don't be afraid to fail" but then when they do, and do so badly, there is barely anything that really provides an in-depth post-mortem…Take, for instance, this piece of puffy garbage about Sophia Amoruso, which purports to inform readers about what Ms. Amoruso learned from Nasty Gal's rapid decline into bankruptcy. Instead it provides some evergreen inspirational advice that applies to virtually...well...everything and anything. TOTALLY USELESS.

Apropos, the above-cited Fast Company piece is lip service Exhibit B. The piece notes:

Tamara Mellon cofounded Jimmy Choo with, well, Jimmy himself back in 1996. But in 2016, she decided to launch her own eponymous luxury shoe brand. It wasn’t easy, though: When she tried to go to high-end factories in Italy, she discovered that many refused to work with her, citing non-compete clauses with the Jimmy Choo brand.

But through persistence, she prevailed, and found factories that made shoes for other luxury brands.

We gather that what happened earlier in 2016 wasn’t relevant to the PR piece. Curious: is “persistence” a new euphemism for “bankruptcy”?

**If we understand what happened here correctly, other existing equityholders tried to recharacterize Ms. Mellon’s term loan holding as equity, effectively squashing her priority secured claim and demoting that claim to equal to or less than the equityholders’ claims. If successful, Ms. Mellon would not have been able to swap her debt for equity. Moreover, the other equityholders would have had a greater chance of a recovery on their claims. They failed, presumably recovering bupkis.