We (STILL) Have a Feasibility Problem (Long the “Two-Year Rule”)

Payless ShoeSource Files for Chapter 11. Again.

Man. That aged poorly AF.

That’s one + two + three…yup, three total “success” claims and that’s just the heading, subheading and intro paragraph. EEESH. This has turned into the bankruptcy equivalent of Oberyn Martell taking a victory lap in the fighting pits of King’s Landing.

And, sadly, it almost gets as cringeworthy:

Of course, we obviously know now that the Payless story is about as ugly as Oberyn’s fate.

Payless is back in bankruptcy court — a mere 18 months after its initial filing — adorning the dreaded Scarlet 22. It will liquidate its North American operations, shutter over 2000 stores, and terminate nearly 20k employees. All that will remain will be its joint venture interests in Latin America and its franchise business — a telltale sign that (a) the brick-and-mortar operation is an utter sh*tshow and (b) the only hope remaining is clipping royalty and franchise fee coupons on the back of the company’s supposed “brand.” And so we come back to this:

That’s right. We have ourselves another TWO YEAR RULE VIOLATION!!

Okay. We admit it. This is all a little unfair. We definitely wrote last week’s piece entitled, “💥We (Still) Have a Feasibility Problem💥,” knowing full-well — thanks to the dogged reporting of Reuters and other outlets — that a Payless Holdings LLC chapter 22 loomed around the corner to drive home our point. Much like Gymboree and DiTech before it, this chapter 22 is the culmination of an abject failure of epic proportions: indeed, nearly everything Mr. Jones stated in the press release reflected above proved to be 100% wrong.

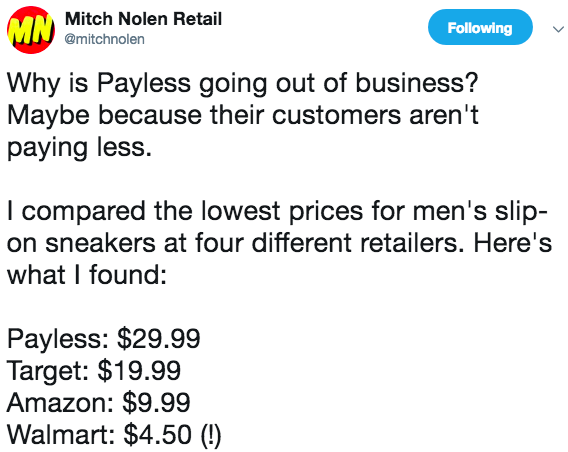

Let’s start, given a dearth of new financial information, with the most obvious factor here as to why this company has round-tripped into bankruptcy — destroying tons of value and irreversibly hurting retail suppliers en masse along the way. In the company’s financial projections attached to its 2017 disclosure statement, the company projected fiscal year 2018 EBITDA of $119.1mm (PETITION NOTE: we’d be remiss if we didn’t highlight the enduring optimism of debtor management teams who consistently offer up, and get highly-paid investment bankers to go along with, ridiculous projections that ALWAYS hockey stick up-and-to-the-right. Frankly, you could strip out the names and, in a compare and contrast exercise, see virtually no directional difference between the projected revenues of Payless and the actual revenues of Lyft. Seriously. It’s like management teams think that they’re at the helm of a high growth startup rather than a dying legacy brick-and-mortar retailer with sh*tty shoes at not-even-discounted-for-sh*ttiness prices.

On what realistic basis on this earth did they think that suddenly — POOF! — same store sales would be nearly 10%.

Seriously. Give us whatever they’re smoking out in Topeka Kansas: sh*t must be lit. Literally.

So what did EBITDA actually come in at? Depending on which paragraph you read in the company’s First Day Declaration filed in support of the chapter 22 petition: negative $63mm or negative $66mm (it differs on different pages). For the mathematically challenged, that’s an ~$182mm delta. 🙈💩 “Outstanding leadership team,” huh? The numbers sure beg to differ.

This miss is SO large that it really begs the question: what the bloody hell transpired here? What is this dire performance attributable to? In its 2017 filing the company noted the following as major factors leading to its bankruptcy:

Since early 2015, the Debtors have experienced a top-line sales decline driven primarily by (a) a set of significant and detrimental non-recurring events, (b) foreign exchange rate volatility, and (c) challenging retail market conditions. These pressures led to the Debtors’ inability to both service their prepetition secured indebtedness and remain current with their trade obligations.

The company continued:

Specifically, a confluence of events in 2015 lowered Payless’ EBITDA by 34 percent—a level from which it has not fully recovered. In early 2015, the Debtors meaningfully over purchased inventory due to antiquated systems and processes (that have since undergone significant enhancement). Then, in February 2015, West Coast port strikes delayed the arrival of the Debtors’ products by several months, causing a major inventory flow disruption just before the important Easter selling period, leading to diminished sales. When delayed inventory arrived after that important selling period, the Debtors were saddled with a significant oversupply of spring seasonal inventory after the relevant seasonal peak, and were forced to sell merchandise at steep markdowns, which depressed margins and drained liquidity. Customers filled their closets with these deeply discounted products, which served to reduce demand; the reset of customer price expectations away from unsustainably high markdowns further depressed traffic in late 2015 and 2016. In total, millions of pairs of shoes were sold below cost in order to realign inventory and product mix. (emphasis added)

You’d think that, given these events, supply chain management would be at the top of the reorganized company’s list of things to fix. Curiously, in its latest First Day Declaration, the company says this about why it’s back in BK:

Upon emergence from the Prior Cases, the Debtors sought to capitalize on the deleveraging of their balance sheet with additional cost-reduction measures, including reviewing marketing expenses, downsizing their corporate office, reevaluating the budget for every department, and reducing their capital expenditures plan. Notwithstanding these measures, the Debtors have continued to experience a top-line sales decline driven primarily by inventory flow disruption during the 2017 holiday season, same store sales declines resulting in excess inventory, and challenging retail market conditions. (emphasis added).

Like, seriously? WTF. And it actually gets more ludicrous. In fact, the inventory story barely changed at all: the company might as well have cut and pasted from the Payless1 disclosure statement:

The Debtors also faced an oversupply of inventory in the fall of 2018 leading into the winter of 2019. As a result, the Debtors were forced to sell merchandise at steep markdowns, which depressed margins and drained liquidity. Customers filled their closets with these deeply discounted products, which served to reduce customer demand for new product. In total, millions of pairs of shoes were sold at below market prices in order to realign inventory and product mix. (emphasis added)

As if that wasn’t enough, the company also noted:

The delayed production caused a major inventory flow disruption during the 2017 Holiday season and a computer systems breakdown in the summer of 2018 significantly affected the back to school season, leading to diminished sales and same store sales declines.

Sheesh. Did the dog also eat the real strategy? Bloomberg writes:

The repeat bankruptcies are a sign the original restructuring may have been rushed through too quickly or didn’t do enough to solve the retailers’ industry-wide and company-specific problems.

And this quote, clearly, is dead on:

“One of the easiest ways to waste time and money in Chapter 11 is to use the process only to effect a change in ownership but not to take the time and protections afforded by the bankruptcy process to fix underlying operations,” Ted Gavin, a turnaround consultant and the president of the American Bankruptcy Institute, told Bloomberg Law.

This begs the question: what did the original bankruptcy ACTUALLY accomplish? Apparently, it accomplished this pretty looking chart:

And not a whole lot more.*

The company also failed to achieve another key strategic initiative upon which its post-bankruptcy business plan was based: investment in its stores and the deployment of omni-channel capabilities that, ironically, would make the company less dependent upon its massive brick-and-mortar footprint. Per the company:

…the Debtors’ liquidity constraints prevented the Debtors from investing in their store portfolio to open, relocate, or remodel targeted stores to keep up with competitors.

And:

Moreover, Payless was unable to fulfill its plan for omni-channel development and implementation, i.e., the integration of physical store presence with online digital presence to create a seamless, fully integrated shopping experience for customers. As of the Petition Date, the completion of this unified customer experience has been limited to approximately two hundred stores. Without a robust omni-channel offering, Payless has been unable to keep up with the shift in customer demand and preference for online shopping versus the traditional brick-and-mortar environment.

In other words “success” really means “still too much effing debt.” This would almost be funny if it didn’t tragically end with the termination of thousands of jobs of people who, clearly, mistakenly put their faith in a management team so entirely in over their heads. Literally nothing was executed according to plan. Nothing.

Seven months after emerging from bankruptcy the company was already in front of its lenders with its hand out seeking more liquidity. Which…it got. In March 2018, the company secured an additional $25mm commitment under the first-in-last-out portion of its asset-backed credit facility. What’s crazy about this is that, never mind the employees, the supplier community got totally duped again here. In the first case, the debtors extended their suppliers by ONE HUNDRED DAYS only for them, absent critical vendor status, to get nearly bupkis** as general unsecured claimants. Here, the debtors again extended their suppliers by as much as 80 days: the top list of creditors is littered with manufacturers based in Hong Kong and mainland China. Who needs Donald Trump when we have Payless declaring a trade war on China twice-over? (PETITION NOTE: we know this is easier said than done, but if you’re a supplier to a retailer in today’s retail environment, you need to get your sh*t together! Pick up a newspaper for goodness sake: how is it that the entire distressed community knows that a 22 is coming and yet you’re extending credit for 80-100 days? It’s honestly mind-boggling. The company cites over 50k total creditors (inclusive of employees) and $225mm of unsecured debt. That’s a lot of folks getting torched.)

Some other notes about this case:

Liquidators. Much like with Things Remembered and Charlotte Russe, they mysteriously have bandwidth again such that they no longer need to JV up as a foursome as they did in Gymboree. Instead, we’re back to the slightly-less-anti-competitive twosome of Great American Group LLC ($RILY) and Tiger Capital Group.

Kirkland & Ellis. There’s something strangely ironic here about the fact that the firm went from representing the company in the chapter 11 to representing its liquidators in the 22. Seriously. You can’t make this sh*t up.

Independent Directors. Here we go again. Remember: the Payless 11 led us to Nine West Holdings which led us to Sears Holding Corp. ($SHLD). We have documented that whole string of disasters here. In the first case, Golden Gate Capital and Blum Capital got away with two separate dividend recaps totaling millions of dollars in exchange for a piddling $20mm settlement. Moreover, to incrementally increase the pot for general unsecured creditors, senior lenders had to waive their deficiency claims that would have otherwise diluted the unsecured pool and made recoveries even more insubstantial. So, here we are again. Two new independent directors have been appointed to the board and they will investigate whether controlling shareholder Alden Capital Management pillaged this company in a similar way that it has reportedly and allegedly pillaged newspapers across the country.***

Fees. If you want to quantify the magnitude of this travesty, note that the first Payless chapter 11 earned the following professionals the following approximate amounts:

Kirkland & Ellis LLP = $4.995mm

Armstrong Teasdale LLP = $495k

Guggenheim Securities LLC = $6.825mm

Alvarez & Marsal = $1.9mm

Munger Tolles = $898k

Pachulski Stang Ziehl & Jones LLP (as lead counsel to the UCC) = $2.5mm

Province Inc. = $2.6mm

Michel-Shaked Group = $560mm

Now THAT was money well spent.****

*Via three separate store closing motions, the company shuttered 686 stores. The second store closing motion proposed 408 store closures but was later revised downward to only 216.

**Unsecured creditors received their pro rata share of two recovery pools in the aggregate amount of $32.3mm, $20mm of which came from the company’s private equity sponsors as settlement of claims stemming from two pre-petition dividend recapitalization transactions. In exchange, the private equity firms received releases from potential liability (without having to admit any wrongdoing).

***Alden Global Capital is no stranger to controversy over its media holdings. In the same week it finds itself in bankruptcy court for Payless, Alden found itself in the news for its reported desire to buy Gannett. This has drawn the attention of New York Senator Chuck Schumer who expressed concerns over Alden’s “strategy of acquiring newspapers, cutting staff, and then selling off the real estate assets of newsrooms and printing presses at a profit.”

***This is but a snapshot. There were several other professionals in the mix including, significantly, the real estate advisors who also made millions of dollars.